Review: Sleuth - A Murder Mystery (1983)

It is a dark and stormy night, and a murder is being committed… John Donleavy has been murdered and the body removed by persons unknown. You are now standing at the door of the Donleavy estate. The door is open.

Our intrepid detective arrives

Sleuth is an adventure mystery puzzle game, where you play as an unnamed detective investigating a murder. The trappings of the game are the stuff of the golden era detective fiction of the 1930s: a mansion in the dark, stuffy rooms filled with the idle rich, and a grisly murder. The goal of the game is to correctly identify the elements of the crime (who, what and where) before time runs out and the villain catches on to your sleuthing. To this end, you the player explore and search the house, examine items and question suspects.

Gameplay

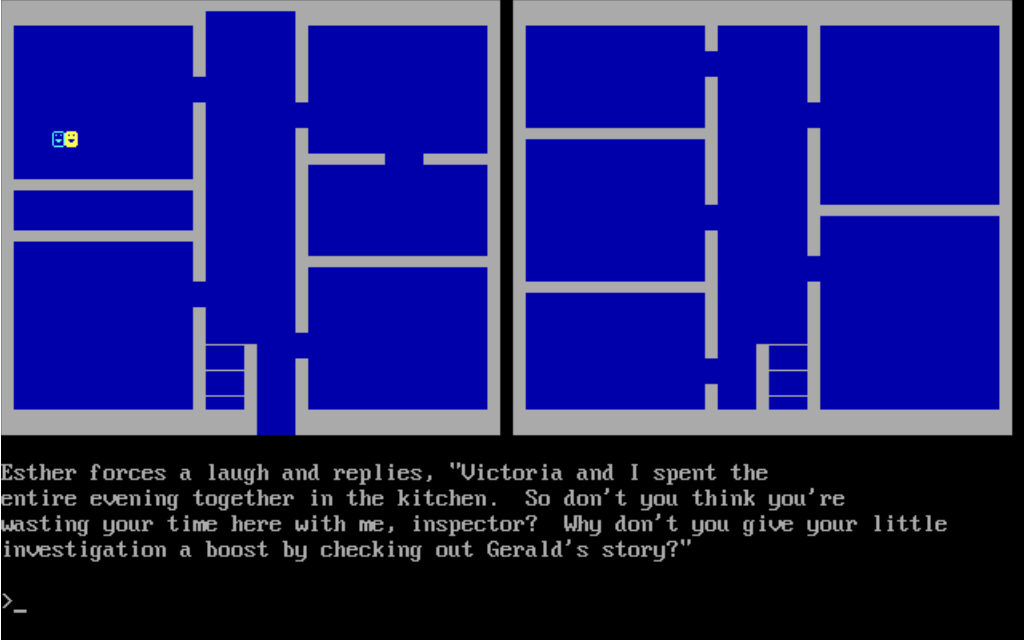

The core gameplay mechanic of Sleuth is exploration, as you have to move your sleuth around the mansion in order to search for clues. Clues are in the form of alibi statements from guests of the house, and specks of blood as observed on the murder weapon and the murder room. Sleuth presents a hybrid graphical/text based interface, with the upper portion of the screen being a map of the mansion where you control your sleuth with the arrow keys and move from room to room and to find items and suspects. The map is the limit of the graphical information, once you are in a room you must type the actions you wish to take, and read the resulting description in the lower portion of the screen. You QUESTION VICTORIA or EXAMINE CANDELABRA or TAKE MAGNIFYING GLASS. This is quite cumbersome, but there are several different aliases for the various commands.1 As you explore the mansion, you uncover where the guest’s alibis fail to align, and discover material evidence. Your goal is the find the murder weapon, gather the suspects at the scene of the crime and make your accusation. Time is of the essence however, for as the evening continues, the murderer’s suspicion grows, eventually reaching the point where they believe killing you is their best way of avoiding capture. There is no in-game mechanism for the player to keep track of the clues they’ve gathered, so you must either remember or take notes.2

Obstacles

Since the enemy of your investigation is time, there are several mechanics included in the game, which on the surface appear to be included simply to waste it.

- Magnifying glass: You cannot accurately identify the murder weapon without a magnifying glass, which each game is placed in a random room of the house. If you are unlucky, the magnifying glass could be in the last possible room, requiring retracing your steps through the other rooms.

- Restless guests: The guests move about the house randomly, and at seemly great speeds (they can beat you to a room on the other side of the mansion, and without being observed!) This means that if you are searching each room carefully, you can encounter a particular guest multiple times before encountering a certain guest even once.

- Silent Treatment: Occasionally when you

QUESTIONa guest, they simply won’t answer you, and you have to ask again. According to the games instructions, this is because the “characters tend to be moody,” but if the mechanic is included for fidelity to mystery tropes, it really falls flat as it neither adds to the immersion nor requires any finesse from the player. - Deaf guests: In order to

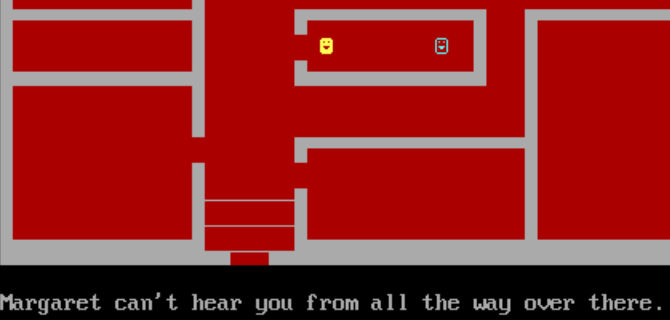

QUESTIONa guest, you have to enter a room and get within a few tiles of them, otherwise they “can’t hear you from all the way over there.” It’s especially frustrating when compared to the fact you canEXAMINEany item in a room from anywhere in the room.

My initial reaction was that each of these elements were completely useless and uninteresting, but it is really only the last two which I find inexcusable. The lack of magnifying glass early provides a slightly interesting strategic challenge, and a savvy player can mitigate the loss through careful play. Similarly having to plan for the travel of guests is at least not boring, my biggest gripe being that the guests appear as if they have portable teleportation devices to travel from room to room.

Comparisons

I’ve most often seen this game compared to Cleudo (a.k.a Clue), and while the trappings and goals between the games are alike, the similarities end there. In Cleudo, the murder mystery and mansion are a pretense for solving a logic puzzle. The cards in the player’s hands representing the “alibis” for the various rooms, people and objects, which by process of elimination, asking questions and observing the answers to other’s questions you can deduce the elements of the crime. The “race” in Cleudo is against the ability of other players to solve the case before you do. Contrast that with Sleuth, where the elements of investigation are more direct, you go to the rooms to EXAMINE evidence that exists in that room. You QUESTION guests about their own alibis. Although more direct than Cleudo, I think it’s that directness which lets Sleuth down a little bit. If I were to be uncharitable, I would characterize the hunt for the murder weapon in Sleuth as “spamming EXAMINE on every item in every room” and finding the murderer is about “spamming QUESTION on everyone.” Solving the mystery is doing the same thing over and over again until you do it on the right thing. Compare this “loop” to sudoku or crossword, where similarly you do the same thing over and over again (answer clues, fill in numbers) but each iteration provides more information and context for each subsequent iteration. I don’t think Sleuth is trying to be that type of game, but I found it easy to be disappointed if I expected it to be a detecting sort of game rather than an exploring type of game.

Rough Edges

I like to be lenient when judging games as old as this one, especially when it comes to user interface and such. Although not everyone will agree, I’m not including the graphics as a rough edge. Although they are quite simple, consisting only of ASCII characters3, they communicate the situation well enough, and I find them rather charming. I will say however, that the lack of graphical decoration within the rooms is initially confusing, especially compared with how guests are represented. I rather like the choice of text as primary mode of communication4, I think a game in this genre is quite at home with text descriptions and narrative, but Sleuth generally errs on the side of having to simple of description. A baby grand piano is “a standard eighty-eight key musical instrument.” The guest room is “decorated in a tasteful oriental style, but looks rather barren.” I suppose each room could only take up a line or two for description given the potential for each room to have a guest, a weapon or both. Even so, possible murder weapon descriptions are terse and underwhelming.

Speaking of murder weapons, one of the most difficult issues for me was what items the game could consider to be the murder weapon. I can completely understand someone using a bust of Mozart, a candelabra or obsidian obelisk could to bludgeon someone to death. But the list of possible murder weapons include a tuba, a paper mâché mask, a backgammon board, and a can of Vichyssoise5.

The game asserts that “Each game is different,” but I feel like the game sacrifices depth in order to provide total possible combinations of outcomes. For example, there are two different mansion layouts, and if you are being extremely generous you could consider there are five possible colors used for the background6, for a total of ten different locations! Each of the two mansions comes with its own compliment of one victim and six guests, but total combinations of possible solutions is not really enough of a selling point if you play the game the same way each time, but it does help. There certainly enough meat on the bones of this game to only have a single solution. I think the inclusion of the customizable guests was a good idea which adds a little novelty to the game.

Diamonds in the rough

Despite the roughness, I found Sleuth enjoyable, even on multiple replays. Although replay value was indeed a selling point, I was skeptical there would be enough to do on a replay. If anything I found that further replays were more interesting as I learned more of the mechanics, and became more familiar with the various rooms and objects: the oboe nestled in the mink rug, the peppermill on the dining room table, the gilded mirror in the master bedroom, each like an old friend.

I can’t be exactly sure, but I’m convinced I’m simultaneously under- and over- estimating the game. By hiding some of the main ways of deducing the scene of the crime, I think the game is artificially extending its life. I won’t spoil it, but when I first discovered one of the ways to tell where the room was I was disappointed and thought the game was “solved” but it wasn’t as bad as I imagined. I think I would need to play it some more to really expose it.

All in all, I was really pleased with this game. It’s not without it’s frustration, but it’s charm overcomes most of that and provides a fun experience and pretty low stakes game to pick up and play every now and again.

Further Reading

Footnotes

-

This command scheme was not uncommon in the text adventure type game, which often suffered from the challenge of gulfing the chasm between the vast breadth of natural language, and the limited ability to parse it back then. I imagine what with the advances in AI these days, you could make a pretty sweet text based adventure game. In any case, in the context of Sleuth it isn’t so bad because there are only five different actions, and two of them are only used once each per game. ↩

-

Another in the tradition of older games entrusting more of the game to the player outside the game itself. I remember drawing many a map and taking many a note when playing games in The Olden Days™ ↩

-

See Code page 437 ↩

-

I couldn’t help but compare this with the quite prolific “hidden object” type of mystery game, where you know what you need to find, and it’s hidden in a visually noisy image. In a text based game, if they player must find an item, then it must be described, but if an item is described, the player finds it. Sleuth avoids this by making the objects in each room obvious and requiring each one be investigated. I’m not sure this is satisfying. A possible solution is to provide a player with a class of object (blunt instrument, a thin flexible object, an item capable of a slashing wound) and they have to pick out items to investigate that might fit the characteristics. ↩

-

As of today, out of stock on amazon.com Also, they have multi-story mansions, but eat their Vichyssoise from a can? Oof, ouch, my suspension of disbelief. For the original Vichyssoie recipe see pages 29 and 59 of Gormet’s Basic French Cookbook by Luis Dat ↩

-

I’m poking fun at it here, but the color change is surprisingly effective at making each play though feel different. ↩